- Home

- David Whellams

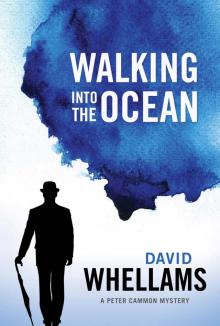

Walking Into the Ocean

Walking Into the Ocean Read online

for Ann and Diana

CHAPTER 1

He stood at the end of the garden lane, alone, waiting. He had once beheaded a sunflower in that same garden.

Chief Inspector Peter Cammon might have been from a work by Magritte. He wore a high-buttoned black suit and a small bowler, also flat black. He held a black umbrella, which might have been mistaken from a certain distance for a walking stick, though the effect was not Chaplinesque. His moustache, trimmed short and neat, added to the impression of compact self-control, though the effect was not Hitlerian; it had long ago turned grey and distinguished.

Another growing season had come and would soon be gone, and the ripe sunflowers, as planned out by his wife, Joan, marched all the way along the snake-rail fence that hemmed the lane. If Cammon, stiff and monochromatic, seemed oddly posed against this backdrop of Impressionist extravagance, the juxtaposition didn’t interest him. He was simply waiting, he told himself, for this latest investigation to begin, that’s all. It was still a fresh morning but warming up fast enough for him to remove his hat and suit coat and fold them over the top of the Gladstone bag at his feet. He regretted bringing the too-formal hat, but leaving it to crown one of the fence posts seemed too capricious a farewell, given how edgy Joan could get when he started a case. The sunflowers did not lead him to think of gardening or marital dissonance or Van Gogh; rather, and he wasn’t sure why, they made him jump to a memory from the last case he had been involved in before his semi-retirement.

As part of that investigation, he had paid a visit to an Alzheimer’s ward in the thin hope of getting information out of an old woman who might, or might not, have seen a killing from her hospital window. Arriving during a routine cognitive test being administered by the hospital psychologist, he watched as the woman misidentified the most ordinary of objects. She thought knuckles were coins and shoelaces were blankets. She responded with such certainty that the psychologist just let her go on, without correction. Peter had ached at her distress; an interview would have been useless. What interested him more and more as he approached the age of sixty-eight was memory itself. After forty years of examining witnesses, he understood that the machinery of the subconscious could spit out a stored image for its own reasons — what counted for a detective was where the recollections led you — yet with this woman the gears had worn through. She had enjoyed looking out her window at the garden, yet what, if anything, imprinted itself on her mind? The tumblers of memory were but a stumbling block away from senility, where memory became a betrayer rather than a faithful guide through the wilds of a difficult universe.

Peter understood that the woman, whom the psychologist let ramble, found solace, from what Peter did not care to guess, by moving into another world entirely. He had no intention of entering her world. He had worked too hard to create his own.

But these were idle thoughts, a warm-up exercise to burn off the morning’s mental fogs while he waited for his colleague to pick him up. They didn’t lead him any further into the incident with the old woman; nor was there any danger that he himself would slip into daftness in the imminent future, although sunstroke was possible in the growing heat of this late September morning.

He had been told enough about his new assignment to book six days in Whittlesun, the coastal town that reluctantly laid claim to the murder-suicide. Sir Stephen Bartleben, who had made the call to him from Yard Headquarters in London and who was the point man for liaising with Whittlesun Police, hadn’t ordered Peter to block in six days, but only suggested it. It probably would not take that long but, Peter knew from experience, there was no way to tell. One presumed the locals were competent, but then again, they had called the Yard for assistance, not the other way round, and so there might be complications of which Peter was currently unaware. On the other hand, wife-murders, and the flight of the husbands, just as often turned out to be routine. Peter would soon know — the degree of complexity, that is. One of his virtues was patience.

André Lasker, a mechanic, had beaten his wife to death and thrown her body off the local cliffs. Or perhaps she had been alive when he pushed her into the Channel. The husband then took off his clothes and walked into the ocean. Her body had been found; his had not.

Sir Stephen Bartleben, who held the title of Deputy Commissioner, had disclosed these simple facts over the telephone. There was never any question of Cammon refusing the assignment, even though he was semi-retired. While it might be said that they had an “understanding” about his availability, Peter Cammon himself was somewhat unsure about his own definition of his status. He had been determined to retire three years ago, then immediately shaky about the decision. Sir Stephen had resisted his departure, for it implied that he ought to be next; they were of the same generation, if not the same class. Their careers had paralleled, though Peter was the field operative and Sir Stephen’s role was to back him up from the remove of London. Peter had worked on contract seven months out of the last twelve, and since leaving his post he had spent about half his time freelancing for the Yard. Yesterday, Bartleben had assumed full cooperation; he would not have called otherwise.

Peter hadn’t asked for details over the phone. Tommy Verden, his friend and frequent partner, would have an information packet with him. Peter would read it over in the car during the two-hour drive to Whittlesun.

The more problematic question was why the boss was sending Peter in particular. There were probably more diplomatic, and younger, choices for a routine case like this one. Within the Yard culture, Peter was notorious for working solo. He cooperated when necessary, and he had a fondness for the collaborative work of forensic analysis, and after a second glass of ale would offer speculation as blue sky as anyone’s in the halls of Scotland Yard HQ. But he had aggravating habits, such as wandering off on his own to track down peripheral witnesses or tying up crime scenes for long periods, driving local authorities crazy. Bartleben was used to fending off complaints from regional police chiefs.

And Bartleben had explained, if only in selective part, one startling feature of this case that might quickly increase the potential for friction. Over the phone, he had gone out of his way to say, “Oh, yes, one of the reasons they could use a little help is that the police in Southwest Region, along the coast, are a bit preoccupied with finding a serial murderer. See Inspector Maris in Whittlesun as soon as you get there. Sounded frazzled over the phone. Good luck.”

Tommy Verden arrived fifteen minutes behind schedule and apologized mildly. He placed Cammon’s grip in the back but didn’t open the door for him. Years ago such a formality might have been expected, but now, Tommy felt, such a gesture would represent condescension to Peter’s ineluctable age. Cammon was the most amiable of superiors, but respect, in the right forms, was still key to their working relationship, and so he didn’t hold the door.

As Verden left the cottage, Peter looked back down the lane. The house was out of view and he did not expect to see Joan, but he turned anyway. Their understanding required no ritual parting gestures, yet he looked out of formal respect for her, even though she couldn’t see him doing it. He did note the flowers again before they drove away. He had topped the doddering sunflower in a flash of anger one evening during the latter days of the Yorkshire Ripper affair. In 1981, Peter Sutcliffe, a lorry driver and sometime factory worker, was finally arrested after murdering thirteen women in Britain, but not before a massive, unprecedented manhunt had been launched and had drawn in — and exhausted — every police force in the country, including New Scotland Yard. Inspector Cammon had worked on the investigation for fifteen months. One day the insanity had followed the weary detective home. It was a time when no one was safe, he had judged — not Joan, not civilization, not fields of in

nocent sunflowers. But the farcical act of decapitating the flower (dead-heading was too laden a term) had pulled him out of his anger, and he was fresh at work the next morning.

Peter forgot all about gardens as they accelerated away from the lane. Verden passed the sealed packet over the headrest. Peter ripped it open and began reading. Tommy drove fast, as he always did, but did nothing sudden that would jog his friend out of his concentration, which was total. He wasn’t offended by Peter’s silence; besides, he had already read the file.

Peter read steadily for an hour. It wasn’t significant that he sat in the back; he merely needed the room to lay out the contents of the envelope. Otherwise, he and Tommy would have shared the front seat and theorized the whole way about the bare-bones facts of the Lasker case. For now, he stayed silent. As they shot up the slip road onto the motorway, Verden could hear Peter behind him, grunting while he thumbed the file. Tommy had started out as a constable and was content in an inspector’s career. Thick-shouldered and dead-eyed, but alert and quick as well, he was a reliable backup to field officers like Peter Cammon. He downplayed his physical strength; Sarah, Peter’s daughter, described him as a “quiet grizzly bear.” He usually wore neat flannels and a casual tweed jacket, which somehow seemed just the right uniform for a man who was willing to please but was also aware of his ability to break your neck.

Peter lowered the sheaf of papers and photographs. He and Verden hadn’t been in touch for months, but their habits were set. Verden had worked with Peter for thirty years but he often began conversations formally. “What do you think, sir?”

“The beaches,” Peter said.

“Thought you would notice that,” Verden replied, looking in the rear-view mirror.

Peter thought of telling Tommy to pull over so that he could move to the front seat, but he held back.

“Tommy, do they mean that the husband dumped the wife on one beach but then walked into the sea at a different beach?”

“Factually true. The way I’ve experienced it, you cannot throw a body into the surf from the heights and then walk into the waves at the same spot. Hence, two beaches.”

“Yes, but if your object were suicide, wouldn’t one method do as well as another, even if you had a particular modus terminus in mind at the outset? Following her off the same cliff would be quick, at least.”

“Yes, but keep in mind that women favour certain methods, like poison and gas. Men are willing to be more dramatic.”

It didn’t matter that this made little sense; it was warm-up banter, to get the conversation moving. Did Tommy think that walking into the sea was more dramatic than a swan dive off a windswept cliff? It could depend on which Gothic romance he was reading, Peter supposed; as a regular driver for Sir Stephen, Verden had a lot of time to read. He leaned across the seat back so that Tommy wouldn’t have to crane his neck.

“Go on.”

“In my experience, it’s men who pursue the stagy scenarios. I’m talking dramatic in the sense of melodramatic. But once they plan their exit, men think they have to follow the framework to the letter, so to speak. Lasker folded his clothes and left them in a neat pile. That had to be pre-planned, he had the image in his head. Somehow he found himself on top of the cliff but he felt compelled to stick to the idea of walking naked into the sea. Jesus, Peter, you’re the English Lit specialist.”

Peter saw where his colleague was heading with this. Lasker had indeed planned a showy exit and had stuck to the scheme, the kind of drowning Byron or Hardy would have appreciated. Perhaps André was making a statement, although the message was as yet obscure. It was hard to imagine someone piling up his clothes and jumping off a cliff, naked. That scenario flirted with farce. Thus, he must have selected a spot along the shore where he could wade gradually into the sea. Peter appreciated the logic of the plan, but his instincts weren’t buying it. It took a cold killer to toss his victim off a precipice and then drive away.

Still, did Lasker confuse himself? Did he lash out at her, improvise her disposal and then go back to the original plan? Peter had no idea of the answers. Of course, if it had all been planned, then there was no farce and no happenstance, only deadly calculation.

Or had André Lasker faked his own death?

By the time the sea came into view, Peter had finished reading the file. He instructed Tommy to drop him off at the shore, as near as possible to the strip where the murderer had walked into the Channel. Tommy would leave his bag at the hotel, the Delphine, off the high street. Peter could walk into town when he was finished; he was sure that the centre of Whittlesun wouldn’t be far from the beach.

They found the tourist beach by following the posted signs. The poured cement parking area that extended out onto the shore contained only one other car, and Tommy was able to loop around the lot without doing a three-point backup. He offered no parting advice when Peter opened the door and got out with his umbrella and, reluctantly, the bowler. Verden had driven Peter hundreds of times, often as an active partner, just as often as a drop-off service, but he never told anyone, including Joan, with whom he was good friends, that he found these partings a little bizarre. The protocol was clear when Peter worked alone. He got into these distant, impenetrable moods at the beginning; no one should try to interfere, Tommy knew. He wasn’t afraid for his colleague, and he expected to hear from him soon, but he would check the valise to see if Peter had brought along that ancient Smith & Wesson. But Peter Cammon ruminating against the backdrop of a cold, lonely sea — that was just about perfect, Tommy thought as he drove off.

His old knees popping, Peter scrooched down on the pebble strand of Lower Whittlesun Beach and looked out to the calm English Channel. A family of four, the owners of the sedan, with their rickety fold-up chairs and primary red and yellow plastic buckets and spades, traipsed towards the parking slab, giving him a look as they passed, as if he were responsible for their bruised feet. He ignored them. Like everyone else, he endured England’s shape-shifting weather with stoicism. Right now the sea was the colour of worn-out pewter, with a lowering sky to match. He heard the motor start up behind him. Alone now, he stared out to a flat, unpromising horizon. It did not take long for a heavy melancholy to settle on the shore. This was a place for disappointed tourists, and perhaps for lonely individuals with desperate plans. Even as his joints stiffened, he continued to examine the sea.

Whittlesun claimed two beaches, each providing half a tourist site. The stony one here, murder on a bather’s heels, nonetheless offered a calm, wadeable sea. Way off to his left, he knew, beyond an obstructing promontory, lay a narrower beach of sand; however, his package of notes warned that it backed up against crumbling cliffs and ran steeply into choppy, treacherous waters. Anna Lasker had fallen into the tide at this point. He had a clear view of about a half-mile in each direction. To his right, the shore ended at a long, wooden pier; the massif bracketed the left extreme. He could see a ruined church on the clifftop.

If Lasker hadn’t been washed out irretrievably, the sea would serve as its own net and cough up the body eventually. With his pointed index finger, Peter drew an arc, a decisive line across the near horizon from land point to point, penning the zone of investigation into an area about a nautical mile wide, from the promontory to the pier. What had happened out beyond this perimeter would likely remain unknown until Lasker crossed back into this zone, one way or another.

How did it feel striding out to the vanishing point, until the salt water closed over your head? Was the urge to swim irresistible? The metaphor became literal: swim or sink. At what point did your decision become unretractable, André?

He had spent enough time here for the moment. He had just wanted to take a look, gain an impression. He creaked to his feet but remained focused on the Channel for an extra minute. What made Peter Cammon a good detective was a kind of free-roaming patience (Bartleben’s phrase); he was willing to stare at a scene without knowing what he was looking for, until something lodged in his mind, even if only in

his subconscious. Not many detectives were willing to partner with him.

Did you plan your walk into the depths for a day like this one, André? Not likely. Verden was right: you followed a tight schedule shaped by more compelling forces than the weather.

Just one more minute, he decided. The tide was moving in by detectable inches. The wind had come up to create distinct waves. Dickens might have had this place in mind when he described “the waves of an unwholesome sea.” Matthew Arnold had imagined “the grating roar of pebbles” in the tidal flow, although he had been talking about religion, the Sea of Faith retreating.

He shook his head in an effort to reset his thinking. He had once regarded homicide in almost literary terms. Whether or not he was naturally inclined this way from four years at Oxford, he came to understand that most criminal acts were sordid and unimaginative. Violent, driven men followed classic patterns — not to mention that they told themselves cheap stories to justify their deeds — and his task was to follow the storyline back to the standard founderous bog of greed, envy, ambition and the breakdown of self-control. In other words, Peter Cammon was a romantic, always searching out the melodrama. His febrile mind had served him well in the early years. Young Inspector Cammon proved instrumental in solving several revenge crimes back then, including three killings by the Kray organization. The murders, and a bank robbery in Durham, had made his reputation. Rapid promotion had followed.

But it was also his duty, he came to realize after a few years, to try to comprehend the hot anger at the core of most crimes. Some dismissed this darkness as imponderable, but he saw that the attacker’s rage and the victim’s terror clashed on a tilting plane, where pain and hope rose and fell, and that was where the uniqueness of each case would be found. The anger and the terror had to be engaged before he could parse the criminal act.

André, did you begin that night in hot anger? Did you run from the horror into the shallow waves, fearing to meet the undertow? Did the chill sea then turn passion to panic?

The Verdict on Each Man Dead

The Verdict on Each Man Dead The Drowned Man

The Drowned Man Walking Into the Ocean

Walking Into the Ocean